Urological

Causes of Chronic Pelvic Pain

Many urological problems can be

involved in causing chronic pelvic pain either separately, or in combination

with other gynaecological and gastrointestinal causes. The list shown

below describes the possible urological problems which may lead

to chronic pelvic pain.

- Chronic

or recurrent infections

- Interstitial

cystitis

- Urethral

syndrome

- Stone /

urolithiasis

- Urethral caruncle

- Urethral diverticulum

Despite this long list, the most

common and distressing conditions seen in a chronic pelvic pain clinic are

interstitial cystitis, and the urethral syndrome. They are frequently seen

with other conditions including IBS, endometriosis and vulvodynia

Interstitial cystitis

Skene first described interstitial

cystitis in 1887. With endometriosis and IBS they make the most common three causes of chronic pelvic pain. Interstitial cystitis denotes a recurring or

chronic condition characterised by increased frequency, urgency, dysuria,

nocturia and a sense of incomplete emptying of the bladder. In some cases

patients present with lower abdominal pain, with no related urological

symptoms [Clemons et al, 2002 and Parsons

et al, 2002]. Painful intercourse, as

well as postcoital pain are also common. All symptoms can get worse

during or before menstruation. It has been recommended by the International

Continence Society to refer to the disease as painful bladder syndrome.

Historically, interstitial cystitis was

not considered as a possible cause of chronic pelvic pain in the gynaecology

clinic. However, recent reports changed this view and it is now considered one

of the most common causes of such pain in gynaecological patients [Stanford et al, 2007]. Health-screening programmes showed

that women between the ages of 40-59 years were most affected. A distressing

effect of the disease was reflected by the fact that two thirds of the affected

women reported impairment of their quality of lives [Temml C, 2006]. Lack of sleep is a major factor here, as it leads to following day fatigue, loss of productivity, depression, hence impaired quality of lift.

The exact cause for interstitial

cystitis is not known, but occasionally patients give history of pelvic

surgery, trauma or recurrent urinary infections. Several theories have been put forward as immediate causes for the problem including:

- Irritation of the bladder wall, surrounding muscles and nerves due to damage to the bladder lining,

- Dysfunction of the pelvic floor muscles that control micturition,

- Autoimmune damage of the bladder wall as part of a general autoimmune problem,

- Damage to the bladder wall following local allergic reactions.

The background factors leading to bladder wall damage have been suggested to be microbiological,

immunological, local mucosal as well as other yet unidentified factors, as suggested by Kelada and Jones in 2007. Many patients have some form of

allergy, and 40% suffer from IBS. In fact, IC may be a presentation of other common problems including lupus, fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome. In many patients symptoms may get

worse after smoking. Paulson

and Delgado [2007] have

examined the special association of interstitial cystitis and endometriosis.

They studied 162 patients with chronic pelvic pain for that purpose. Their

results showed 76% (123/162) of the patients had endometriosis, whereas 82%

(11/162) had interstitial cystitis. Both pathologies were diagnosed

simultaneously in 66% (107/162) of the patients. This is a very strong

association which entails looking for the other pathology, if either of them has

been diagnosed.

Recent reports indicated that 5-6/10000

patients may be inflicted in the general population with 10:1 female to male

ratio. Furthermore, there may be some genetic or familial predisposition, as

interstitial cystitis is more common in women with similar first-degree family

history. In fact 35% of patients with interstitial cystitis reported urgency or

frequency in female relatives.

Repeated urine examinations usually give

sterile cultures. Stamford

and McMurphy (2007)

confirmed urinary tract infections in only 6.6% of these patients. On the other

hand, pelvic examination may reveal a tender bladder bed and gives some

clues to the diagnosis. However, there are no specific ultrasound diagnostic

findings but bladder site-specific tenderness can be elicited with the probe

during tansvaginal scan examination. Cystoscopy may reveal reduced bladder

capacity, even under general anaesthesia, but this is not a diagnostic

criterion. Bladder wall pathology is characterised by fissures or rupture of

the surface epithelium when the bladder is distended. This exposes the

underlying nerve endings to the irritating chemicals in urine which may offer

an explanation for the pain suffered by these patients when the bladder is

full. It may as well show small blood vessels which usually rupture during

the second bladder filling during cystoscopy leading to petechial submucosal

haemorrhages called glomerulations. However, over distension of the bladder can lead to similar findings in normal women with no bladder symptoms. This puts more emphasis on taking bladder wall biopsies than relying totally on

this finding. Hunner's ulcers may be seen in 10-50% of the cases, and this

version is called classical interstitial cystitis in comparison to the

non-classical version with no such ulcers. Bladder wall biopsies can show

normal findings in the non-classical type. However, inflammatory areas with

lymphocytes, plasma and mast cells are common in the classical group.

Despite all effort for a positive

diagnosis, the final diagnosis is usually one of exclusion [Kelada

and Jones, 2007].

|

|

- The first hysteroscopic image above shows multiple glomerulations, which are small bleeding vessels,following rapid emptying of the bladder. In the absence of Hunner's ulcers, it may be advisable to take bladder wall biopsies to check for inflammatory cells.

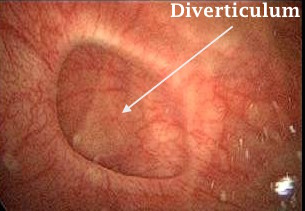

- The second hysteroscopic image show a bladder wall diverticulum. The bottom of the diverticulum should be inspected hysteroscopically for presence of mass, ulcer, stone or any other pathology.

Interstitial cystitis treatment

No specific treatment is yet available, and all attempts should be made to control the intensity and duration of the attacks. Changing life style is the first step patients should take to relieve their symptoms. Stress control through exercise and warm bath, reducing alcohol intake and abandoning smoking are all important. There is no verified diet to use, or type of food to avoid. Patients should take note of when their symptoms flare in relation to the meals they have taken. However, tomatoes, citrous fruits and excessive caffien use have been mentioned by many affected patients as predisposing factors.

Supportive methods

Before, or while taking any medication for IC, supportive therapies can, and should be used to help with symptoms control.

- Bladder retraining, also known as bladder drill, can be used to re-educate the bladder to void by the clock at fixed intervals, rather than following an urge. The time in between voiding can be increased according to the patient's response and tolerance.

- Physiotherapy under the direction of a trained physiotherapist, at least initially, can be helpful in reducing bladder wall strain, by massaging the pelvic wall muscles.

- Using transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation [TENS] can help in relieving bladder pain by sending electrical impulses into the body. These can be useful for strengthening the muscles, improve blood supply and reduce pain. This machine is battery operated, readily available, and can be used unsupervised.

- Psychological counselling and support can also be useful in helping patients to come to terms with their symptoms. However, there is usually some reluctance in accepting this advice, as much as patients reject using anti depressants.

Medical methods

Many oral and local bladder instillation

remedies have been described for the treatment of interstitial cystitis. This reflects our lack of proper understanding of the involved pathology, and hence the inclination to use empirical treatment without proven benefit. At

the same time, as flares of interstitial cystitis are usually self-limiting, response to any medication can be coincidental and over emphasised.

Oral medication used regularly for the

treatment of interstitial cystitis includes:

- Pentosan polysulfate

[elmiron] 100-200 mg twice daily between meals

- Tricyclic

antidepressants [amitriptyline]

- H1 receptors

antagonists are useful in reducing symptoms. Atarax in a dose of 25 mg every

night should be the starting dose. This could be increased to 50 mg and

maximally to 75 mg if tolerable.

- H2 receptors

antagonists [cimetidine] could reduce all symptoms including nocturia.

- Bladder spasmolytics

[oxybutinin]

- Short term use of

narcotic analgesia only in cases of severe pain

Pentosan polysulfate is a

polyanionic analogue of heparin which can be used to reduce pelvic pain and

urinary symptoms except nocturia. Its exact mode of action is not known but it can form a water coating over the bladder epithelium, which acts as a substitute

for the defect in glycosaminoglycan layer [GAG]. A meta-analysis study

published by Dimitrakov et al in 2007 confirmed a modest efficacy of pentosan polysulfate in

this respect, with a relative risk of 1.78 for patients to report symptomatic

improvement. This same study suggested some efficacy of the tricyclic

antidepressant amitriptyline in reducing symptoms caused by interstitial

cystitis. This can be expected, as tricyclic antidepressants are capable of

controlling chronic neuropathic pain even in the absence of clinical

depression. Furthermore, only small daily doses are needed, compared to the

doses used to treat depression. However, many patients are reluctant to use

them, but with reassurance and explanation a few may agree to give them a try.

They act as H1 and acetylcholine receptors blockers and serotonin and

norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors.

For patients who suffer with pelvic

pain just before or during menstruation, time contingent oxybutinin medication

can be used. It can be started early during the luteal phase and continued

up to the end of menstruation. A few of these patients may also respond

favourably to progestogens medication during that time. This can be in the

form of progestogen only pill or luteal progestogen supplement.

Other treatment measures included

bladder hydrodistension and instillation of different chemicals into the

bladder. Weekly instillation of 50 ml of 50% dimethyle sulfoxide (DSMO) into

the bladder through a Foleys catheter has been used. The fluid should be

retained in the bladder for up to one hour before being drained, depending on

the patientsí tolerance. Patients should take an analgesic one hour before they

come in for the procedure, as it may be uncomfortable. On the other hand, 10000

IU heparin in 10 ml of sterile water can be instilled into the bladder 3-5

times every week, and retained for one hour each time. Heparin is not absorbed

into the circulation in any significant amounts to cause any haematological

changes. Many other medications have been used with variable results. Patients

should be reminded that it usually takes 6-8 weeks before any improvement in

symptoms can be felt. Furthermore, each of these procedures should be covered

by prophylactic antibiotics. Dawson

and Jamison [2007] have published a meta-analysis of all the studies related to

such treatment modalities. They did not find enough studies to confirm a useful

role to DSMO. On the other hand, they showed that oxybutinin instillation into

the bladder was associated with increased bladder capacity, reduced frequency

and improved quality of life. Similarly some promising evidence was shown for

BCG with less pain reporting and fewer general symptoms. However, more studies

are still needed to confirm the efficacy and role of intravesical instillation

therapy in the treatment of interstitial cystitis. This is especially so since

another meta-analysis study by Dimitrakov

et al in 2007

suggested the efficacy for Pentosan polysulfate in contradiction to the

meta-analysis study reported before.

A combination protocol with both oral

and intravesical medication has been reported by Taneja and Jawade in 2007, with excellent effects. Patients had

intravesical hydrocortisone (200 mg) and heparin (25000 IU) in physiological

saline every week for 6 weeks. In addition patients were given oxybutinin or

tolterodine orally. Refractory or recurrent cases were also given 40 mg

triamcinolone every week for 6 weeks. All patients had some relief within 48

hours, and 73% had almost complete pain relief within the 18 months follow up

period of the study. Intramuscular injections of triamcinolone were needed to

control relapses in 23% of the cases. This is a very promising protocol if it

can be verified by other studies.

Surgical methods

Surgery is rarely resorted to for the management of women with interstitial cystitis, who failed to respond to other forms of treatment. Bladder distension has already been alluded to. This should be done under general anaesthesia, as it can be very painful, otherwise. The saline bag should be kept about 80 cm above the level of the bladder, and the fluid allowed to run to fill the bladder, without applying any form of pressure to the bag. The maximum capacity of the bladder will be reached when saline starts outflowing off the urethra, or it stops dripping from the saline bag. Other surgical procedures less commonly used include laser or diathermy cauterisation of the Huhner's ulcer, Botox injection into the bladder wall, and neuromodulation with an electric implant to reduce urinary urgency.

Urethral syndrome

This is another common urological

cause of chronic pelvic pain. It gives similar symptoms to interstitial

cystitis with the exception of nocturia. Previous history of

infections with chlamydia, mycoplasma and herpes virus are not uncommon.

Stenosis of the urethra from trauma or atrophy is also a factor. It is also seen with other conditions, including vulvodynia and IBS. It can be

distinguished from recurrent bacterial cystitis, as urine cultures are usually

negative, and vaginal examination may reveal a tender robe-like urethra. As

for interstitial cystitis, all acid rich food, caffeine, spices, tomatoes and

artificial sweeteners must be avoided. Adequate hydration should be

maintained, to have diluted non-irritating urine. Treatment is difficult, and entails long antibiotic courses for any isolated bacteria, and urethral dilatation [31

Fr]. In older women vaginal oestrogen cream helps in building up the vaginal,

urethral and trigonal epithelium, and improves symptoms

Few urological symptoms may have a

direct gynaecological origin. As discussed before, endometriosis of the

bladder wall may present with suprapubic pain, urinary frequency,

urgency and rarely haematuria. As well, hypo-oestrogenic women may present with similar symptoms, due to atrophy of the oestrogen dependent

urinary epithelium covering the urethra and trigone. Furthermore,

there is reduction in the submucosal collagen and vascular plexus, which are

important factors in the maintenance of urethral pressure. In such cases 3-weeks courses of vaginal

oestrogen cream may help in building the tissues and alleviating symptoms, otherwise longer treatment may be need in severe cases. A

progestogen will be needed to prevent endometrial hyperplasia, and to have a

withdrawal bleeding in postmenopausal women, especially if repeated treatment

courses were required.

Finally, it is important to remember that almost 25% of postmenopausal women on oral HRT may still have oestrogen deficiency genitourinary symptoms. In these cases, complementary local oestrogen will be needed, as well.