Endometriosis

Endometriosis is the most commonly diagnosed cause of pelvic pain, in areas with low incidence of sexually transmitted diseases. However, other causes should not be neglected just because endometriosis has been seen during laparoscopic examination. This is especially so since a good percentage of patients with endometriosis do not suffer from chronic pelvic pain. Endometriosis is characterised by growth of ectopic endometrial tissues outside the uterine cavity. It has been reported that such tissues posses the enzyme aromatase cytochrome P450, which converts androgens to oestrogens, helping them to maintain their own growth. It is a progressive disease in 30-60% of the cases [D’Hooghe et al, 2003], and may affect 10-15% of the fertile female population. This range may rise to 21-47% in infertile women. The commonest symptom attributable to endometriosis is pelvic pain. This is secondary to local inflammation and scarring, caused by recurrent bleeding episodes within the tissues. Furthermore, direct involvement of small nerve fibres in the pelvis, and tissue ischaemia due to adhesions may be contributing factors. All pelvic organs can be affected, and the symptoms may vary according to the site and extent of the lesions. As a progressive disease, it may affect patients’ lives through chronic pain or infertility related problems, or both. It is not unusual to see patients with a complex scenario of chronic pelvic pain, abnormal uterine bleeding and infertility at the same time.

No age group is immune against endometriosis and young pre-menarcheal girls with chronic pelvic pain were shown to suffer from endometriosis [Marsh and Laufer, 2005]. Teenage girls with severe endometriosis not relieved after 3 months of using the pill and non steroidal anti inflammatory medication were reported to have 70% chance to be suffering form endometriosis. Unfortunately, many medical professionals and parents discard the possibility that teenage girls may develop endometriosis. They adopt an attitude of ‘she will grow out of her pains’. Few will but many will not! Using oral contraceptive pills or other hormones does not cure or eradicate endometriosis. Medical treatment only controls symptoms, but surgery is the only proper treatment. It is important that these patients are referred for specialist advice since endometriosis is a progressive disease, and early treatment may prevent future complications. Because of these delays, it usually takes 6-7 years to diagnose endometriosis, hence a delay in effective treatment as well. The younger the patient at the onset of symptoms, the longer it usually takes before making a diagnosis. In fact more than 40% of patients with endometriosis started being symptomatic during their teenage years. Accordingly, teenage girls with chronic pelvic pain should not be denied proper laparoscopic assessment just on the grounds of their age. It is unfortunate that there are no clinical methods to identify those teenage girls who may develop rapidly progressive endometriosis. A recent review by Song and Advincula [2005] emphasised this point and suggested that early diagnosis and appropriate treatment of chronic pelvic pain in this group of women will significantly improve their future reproductive health outcome. Furthermore, no differences were found in the prevalence of endometriosis in relation to ethnic origin or socioeconomic class [Chatman 1976]. Any suggested differences at that time can be explained by the easy access of certain groups of patients to medical care than others. Consequently, these parameters should not be taken into consideration when suspecting the diagnosis in patients with chronic pelvic pain. It also follows that neither social class nor ethnic origin of the affected patient should dictate the mode or range of investigations. Some reports indicated increased incidence of endometriosis over the years. This can be a relative increase due to better diagnosis and increased availability of laparoscopic surgery. However, it may as well be a real one due to the social tendency in delaying first pregnancy and lower parity. The higher risks posed by increased environmental exposure should not be forgotten.

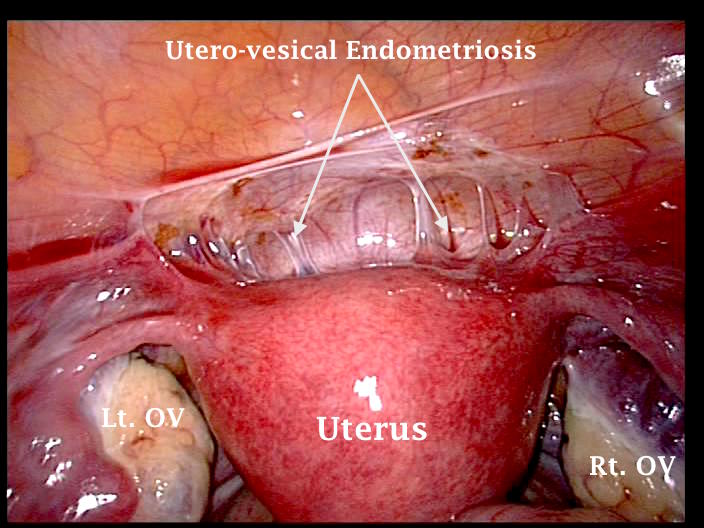

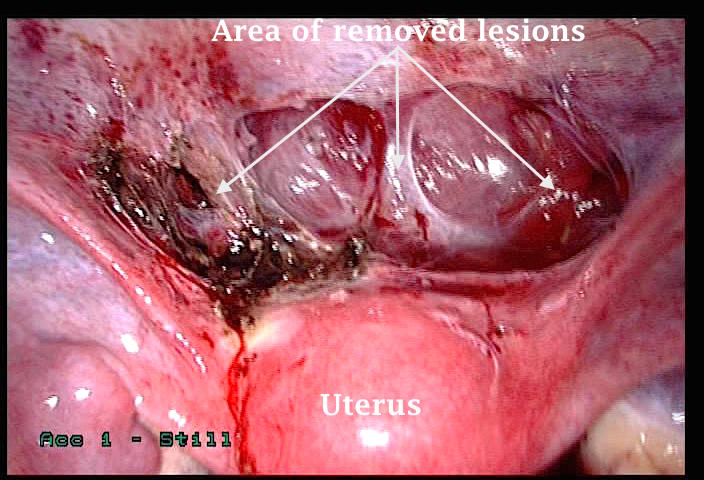

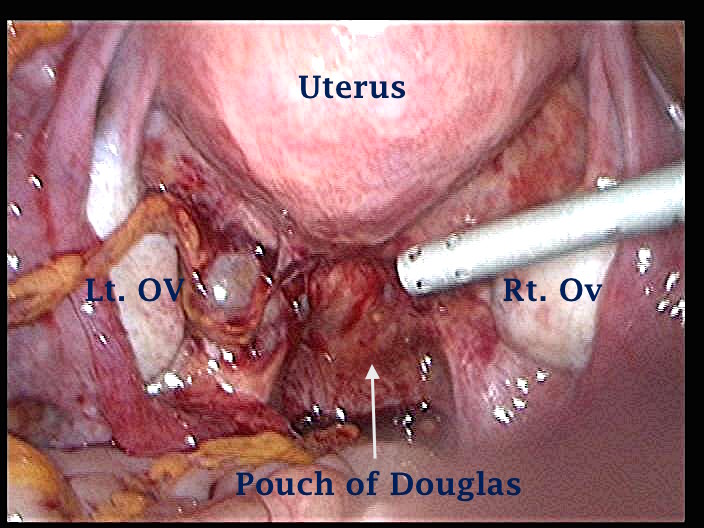

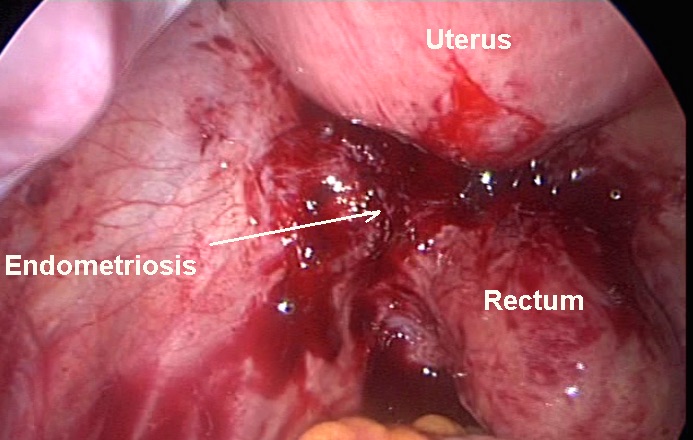

The following two laparoscopic pictures show pelvic endometriosis in two young women in their early 20s. They had bad period pains and bowel symptoms since their early teenage years. Note that black endometriosis usually takes about 7 years to form.

Suspected causes of endometriosis

Sampson first described the term endometriosis and suggested retrograde menstruation as its main cause in 1921. However, over the years such a phenomenon has been shown to occur in 76-90% of all menstruating women [Blumenkrantz et al, 1981 and Kruitwagen et al, 1991] but only a small fraction probably with altered cell-mediated and humoral immunity would develop endometriosis as described by many authors. Furthermore, endometriotic lesions have abundant plasma cells and macrophages which are capable of producing IgM and different tumour necrosis factors which are seen in different autoimmune diseases [Hever et al, 2007]. The same authors showed increased level of B-lymphocytes stimulator in the blood of women with endometriosis. Accordingly, endometriosis has been considered as an autoimmune disease as it is often associated with many autoantibodies and other autoimmune problems. Ulukus and Arici [2005] suggested that decreased peritoneal T- cell and natural killer cell cytotoxicity as well as increased levels of several cytokines and other growth factors to be responsible for induction of ectopic endometrial cells proliferation and increased local angiogenesis. Furthermore, removal of the ectopic endometrial cells was hindered by their inherent resistance against the immune cells. On the other hand, Kalu et al (2007) reported a local role for peritoneal macrophages activating factors in the pathogenesis of endometriosis. They found increased levels of interleukin 6 and 8 as well as monocyte chemotatic protein-1 (MCP-1) in the peritoneal fluid but not in blood samples from the same patients with endometriosis. All these immunological changes were summarised by Podgaec et al in 2007 who described endometriosis as an inflammatory disease involving a shift towards a Th1 immunological response.

However, despite all this immunological work to explain the retrograde menstruation and implantation theory as the cause of endometriosis, finding endometriosis in pre-menarcheal girls with normal internal genitalia supported the idea that other factors may be involved in its development. Furthermore, endometriosis as an autotransplant should be expected to have the same, or at least similar physical and functional characteristics as the eutopic source. This is not usually the case and Redwine DB [2002] showed in a review article some fundamental differences between the two including clonality of origin, enzymatic activity, protein expression as well as histological and morphological characteristics.

Other factors predisposing to the development of endometriosis were covered by the following theories:

1. Metaplasia of the peritoneal cells converting into endometrial tissue has been suggested to explain retroperitoneal endometriotic implants [Myers theory].

2. Blood and lymphatic permeation of the endometrial cells may explain extra-pelvic implants, such as those found under the liver and in the lungs [Halban’s theory].

3. Direct spillage of endometrial cells during surgical operations involving the uterine cavity may explain rectus sheath and abdominal scars endometriosis.

4. Recently retrograde spillage of healthy non-menstrual endometrial cells into the pelvis has been suggested. These cells were alleged to have better chance of attaching themselves to pelvic organs than sloughed menstrual cells.

5. The role of environmental pollution in causing endometriosis has been suspected as endometriosis can be experimentally induced in monkeys by subjecting them to dioxin [Reir et al, 1993], which is a common environmental pollutant. The incidence and severity of the disease was dose dependent. A comprehensive review was published by Rier SE in 2002 using the rhesus monkey as an experimental model. He reported that blood levels of polyhalogenated aromatic hydrocarbons in monkeys with endometriosis were similar or even lower than blood levels documented in the general human population. A long-term immunological change following this exposure was suggested as the cause behind developing endometriosis.

It is evident that none of these theories gave full explanation why some, and not all patients with similar predisposition develop endometriosis. Genetic factors have been explored as the relative risk of endometriosis in a first-degree relative was reported to be 7.2 [confidence interval 2.1-24.3] by Moen and Magnus in 1993. They also found that severe manifestations of the disease were more common in patients with a positive family history compared to those with no such history (26% vs. 12%). A similar finding was also documented by Kashima at al in 2004. They reported a relative risk of 5.7 in sisters of inflicted patients, compared to healthy fertile women. Despite the important familial inheritance role, Wenzl et al in 2003 suggested that multiple candidate genes were also involved in the predisposition to the development of endometriosis. Furthermore, evidence linking endometriosis with loss of several cell cycle regulatory genes has been documented previously by Shin et al, in 1997 and Kosugi et al, in 1999.

The issue was further confused by the suggestion that peritoneal, ovarian and rectovaginal endometriotic lesions are three different entities with different pathogenesis [Nisolle and Donnez, 1997]. The origin of endometriomas for example has special attention as discussed by the same authors. Most authors accepted the surface invagination theory, but both the implantation and metaplasia theories were claimed to be the direct initiating causes. Endometrial tissue implanted on the surface of the ovary invaginates into the ovarian tissue to create the origin of endometriomas is one concept. The other concept is that metaplastic mesothelial cells covering the ovary invaginate into the ovarian cortex, and convert into ectopic endometrial cell. This concept was supported by the finding of a direct continuity between the intraovarian endometrial cells and the invaginated mesothelium. A third concept, which did not attract much support, was published by Jain and Dalton in 1999. They suggested that chocolate cysts may develop from ovarian follicles after serial scan examinations of 12 patients who later had laparoscopic treatment.

It can be summarised that development of endometriosis, as a disease entity, depends on the interaction between many environmental, genetic, familial, anatomical, hormonal and immunological factors. These factors may have different emphasis in different individuals, on the location and severity of the disease and the clinical response of patients as well.

General risk factors for endometriosis

Other than the immunological and genetic factors alluded to, patients with congenital uterine anomalies have increased risk of developing endometriosis. This was thought to be more frequent with non-communicating uterine horns. Furthermore, Rozewicki et al [2005] described a relationship between the anatomical course of the intramural part of the fallopian tubes and the risk of developing pelvic endometriosis. They X-rayed hysterectomy specimens injected with barium sulphate and divided the intramural part of the tubes into tortuous, curved and straight categories. Endometriosis was most frequent in patients with the straight intramural category and least frequent in those with the tortuous pattern. They concluded that a tortuous course of the intramural part of the tube is the normal anatomical finding. On the other hand, the straight and curved categories represented anatomical abnormalities that can predispose women to more retrograde menstruation and the risk of developing endometriosis.

Matalliotakis et al in 2007 reviewed many other risk factors which can also predispose women to develop endometriosis, including:

- Lower body weight

- Alcohol use

- Early menarche

- Short menstrual cycles

- Heavy menstruation

- Low parity

- Family history of cancer.

Many of these risk factors share similar characteristics of uninterrupted cyclic ovulation and regular menstruation. These two are related to excessive oestrogen exposure and chances of more retrograde menstruation. This is in comparison to women who used the combined contraceptive pill for long periods of time, parous women, and those who practiced breast feeding.

With the more liberal use of tamoxifen in the treatment of breast cancer, various reports have been published linking its use with the development of endometriosis in both pre and postmenopausal women [Abad de Velasco and Cano, 2003 and Varras et al, 2003]. Other complications included development of adenomyosis and fibroids [Varras et al, 2003] on top of the well-publicised development of functional ovarian cysts, endometrial polyps and carcinoma. Another important point to bear in mind is the iatrogenic development of endometriosis or recurrence of old lesions in postmenopausal women using oestrogen only HRT. This was noticed even in patients who already had pelvic clearance. Such patients may present with pelvic pain, which may be assumed to be of non-gynaecological cause, as the uterus and ovaries have already been removed.

Gynaecological symptoms related to endometriosis

· Taking symptoms as the starting point, endometriosis was diagnosed in up to 60-75% of women with dysmenorrhoea. The severity of pain here was more likely to correlate to the depth [Koninckx et al, 1991 and Ripps and Martin, 1991] rather than the grade of endometriosis itself. This was confirmed by Muzii et al [2000] who also found no difference in the capacity of red or black endometriotic lesions in producing prostaglandin F2a. As well, endometriosis was diagnosed in up to 50% of patients with deep dyspareunia and the pain intensity here correlated directly with the extent of the uterosacral ligaments involvement [Porpora et al, 1999]. The same authors also found that it was not the size of endometrioma but their association with pelvic adhesions that caused pelvic pain.

· On the other hand, the range of pain sympotmatology in patients with proven endometriosis was examined in a retrospective case-control study reported by Matalliotakis et al in 2007. Pelvic pain, dysmenorrhoea and dyspareunia were present in 79.1%, 70.2% and 49.5% of the cases respectively. The figures for dysmenorrhoea and dyspareunia almost mirrored the corresponding two mentioned above for patients who presented with these two symptoms. This emphasises the need to take these symptoms seriously, especially if they were present together in the same patient. In such cases, there is be a reasonable possibility that endometriosis may be the common underlying cause. Accordingly, a diagnostic work up should be started to exclude this possibility irrespective of the patient’s age.

· Patients with endometriosis may report abnormal uterine bleeding, both as heavy periods and intermenstrual spotting. Heavy periods are usually associated with dysmenorrhoea in these cases. It can be dysfunctional or associated with adenomyosis, fibroids and endometrial hyperplasia. Treatment of endometriosis does not usually have a big impact on the associated bleeding problems. Accordingly, a levonorgestrel-loaded intrauterine device (mirena) is frequently inserted at the time of laparoscopy to reduce the menstrual blood loss. Furthermore, some studies showed that using a mirena device reduced the number of further surgical procedures in women with symptomatic endometriosis.

· Midcycle pain is seen often in patients with endometriosis

It is not unusual for patients with endometriosis to present with infertility on top of their chronic pelvic pain or abnormal uterine bleeding. This is a very important issue and forms a major psychological concern for most young patients with chronic pelvic pain especially those diagnosed with endometriosis, or pelvic adhesions. Many of them proclaim that they can tolerate and live with some degree of pain if their future fertility potential can be guaranteed. Unfortunately, they usually come in with conflicting information regarding this issue from medical or different Internet sources. Furthermore, they demand factual information either positive or negative to allow them to plan their future lives accordingly. This concern may affect their pain threshold and response to medical or surgical treatment, and should be addressed seriously. Parents are not different in this respect and usually raise the question very early during the interview which puts more pressure, especially on young patients who are not old enough to have children, or are not yet in a stable relationship to allow them to do so. This issue should be addressed professionally but sympathetically by all concerned. However, unfortunately the effect of endometriosis on patients’ fertility potential is shrouded with great confusion and myth, as it is not an absolute bar to pregnancy. It is not clear why 30-40% and not all women inflicted with endometriosis have such fertility problems. This is valid even to those women with the same degree of the disease. Accordingly, a short summary of the reported causes of infertility will be discussed below, to help the receiving gynaecologist in the chronic pelvic pain clinic to discuss these issues with the patient and her parents or spouse in a more scientific way if proved necessary:

- Deep endometriotic lesions involving the uterosacral ligaments and pouch of Douglas could cause significant deep dyspareunia reducing the frequency of intercourse. This might result in secondary vaginismus and total apareunia in some cases. Patients should be reassured that addressing this type endometriosis would improve their chances of having a better marital relationship.

- A detrimental effect of the peritoneal fluid from patients with endometriosis on sperm parameters has been suspected for many years. Many authors used different techniques to document such an effect. Using computer assisted semen analysis, Oral et al in 1996 reported 40%, 50% and 80% decline in sperm motility and percentage of progressive motility after 4, 7 and 24 hours incubation with peritoneal fluid from women with moderate or severe endometriosis compared to sperm incubated with peritoneal fluid collected from fertile women without endometriosis. Interestingly, fluid from women with minimal or mild endometriosis, which is expected to be more biochemically active, did not affect these parameters. A different study showed a positive correlation between the peritoneal fluid volume, which is usually increased in women with endometriosis compared to controls, and the reduction in sperm motility parameters [Oak et al, 1985]. Similarly the hamster egg sperm penetration test showed reduced penetration rate by sperm mixed with peritoneal fluid from patients with endometriosis compared to sperm mixed with fluid from fertile controls [Aeby et al, 1996]. Also peritoneal fluid macrophages obtained from women with endometriosis showed increased sperm phagocytic activity compared to similar cells from fertile women without endometriosis [Muscato et al, 1982]. All these authors and many others who reported similar findings came to the conclusion that peritoneal fluid in women with endometriosis might have a detrimental effect in sperm functional ability and their natural fertility potential. However, this was not a universal finding as Sharma et al, in 1999, reported no such detrimental effects, but this seemed to be a minority opinion.

- Altered anatomy due to pelvic adhesions is also an important factor in advanced cases causing mechanical difficulty in sperm and embryo transport. There seems to be general agreement on this point in the literature. However, it is important to remember that the fallopian tubes might be involved with adhesions which could restrict their movement, but are usually patent. On the other hand the ovaries might be adherent to the pelvic sidewall out of the reach of the fimbrial end of the tubes for ovum pickup, Accordingly, tubal patency tests other than by laparoscopy might not be very useful in elucidating any tubal factor in such cases.

- Few articles documented certain endocrine changes leading to anovulation including high prolactin and cortisol levels which could cause dysfunction of the hypothalamo-pituitary-ovarian axis [Lima et al, 2006].

- Increased uterine muscles pulsatile activity has also been described in patients with endometriosis.

- Reduced egg and embryo quality with lower implantation and success rates after IVF treatment cycles were reported in patients with endometriosis. This was valid even during IVF treatment cycle when recipients used eggs donated by women with endometriosis [Pellicer et al, 2001].

- Low expression of secretory phase endometrial integrins, which are cell adhesion molecules, have been reported in some women with endometriosis [Lessey BA, 2002]. This was seen more often in minimal and mild endometriosis than in the more severe forms of the disease despite the endometrium being histologically in phase. Such evidence has been taken to indicate a dysfunctional endometrium with reduced receptivity leading to lower cycle fecundity rates in such patients. Integrins levels were shown to increase after treatment of endometriosis.

- Some reports associated endometriosis with an increased risk of repeated miscarriages though many others denied such an association. Furthermore, Matorras et al in 1998 found no such an association irrespective of the stage of the disease and no improvement in miscarriage rate after treatment of minimal or mild endometriosis. On the other hand an epidemiological review article written by Tomassetti et al in 2006 did confirm an association between endometriosis and recurrent implantation failure after assisted reproductive treatment but showed no evidence of recurrent miscarriage after natural pregnancy. They also suggested that changes in folliculogenesis, ovulation, oocytes quality and early embryonic development as contributing infertility factors in women with endometriosis. They related all these detrimental effects to the humoral and cell mediated immunological problems associated with endometriosis.

It is evident that there is a lot of controversy regarding the effect of the different grades of endometriosis and their mechanism of action on the fertility potential of the inflicted patients. A review published by D’Hooghe et al in 2003 sited the arguments in favour of a causal relationship between endometriosis and infertility as follows:

- There is an increased prevalence of endometriosis in subfertile patients compared to fertile women.

- There is a reduced monthly fecundity rate in women with minimal and mild endometriosis compared to patients with unexplained infertility.

- There is a negative relationship between the stage of endometriosis and both the monthly fecundity rate and crude pregnancy rate

- There is a reduced monthly fecundity rate after insemination with husband or donor sperm in women with minimal and mild endometriosis compared to women with a normal pelvis.

- There is reduced implantation rate per embryo transfer after IVF treatment cycles in women with moderate and severe endometriosis in comparison to women with a normal pelvis.

- There is increased monthly fecundity rate and cumulative pregnancy rate after surgical treatment of minimal and mild endometriosis.

On the other hand, treatment of moderate and severe endometriosis can also improve the monthly fecundity rate [Allaire C, 2006] but in general a negative correlation has been shown between the stage of endometriosis and the spontaneous cumulative pregnancy rate after surgical treatment by few studies. This is a reflection of the point that the higher the grade of endometriosis, the less effective surgery would be.

Irrespective of the outcome of all this controversy, a pragmatic clinical approach should be adopted in such cases. It is important that women with endometriosis should not delay childbearing into their late reproductive years, because of the age related decline in natural fertility. This would help in avoiding immense future disappointments and unnecessary discussions regarding the favourable and unfavourable statistics related to this subject.

Another important issue, which needs special attention, is the frequently asked question regarding the association of endometriosis with all sorts and forms of cancer. The Internet is full of unqualified statements which can be very frightening and demoralising even for women with no, or sporadic family history of any form of malignancy. This was usually a serious concern for many women over the age of 40 years. These are usually demoralised patients who have already suffered from chronic pelvic pain and infertility. To gain the confidence of these patients the receiving gynaecologist should be aware of the real facts related to this subject and should even volunteer the information in certain circumstances as few patients may dread asking the question, though they have already documented their concerns in the pain questionnaire. A recent study which used the Swedish National Inpatient Register which was linked to the National Cancer Register showed increased risk of endocrine and brain tumours, ovarian cancer, as well as non Hodgkin’s lymphoma in women diagnosed with endometriosis. The average age of diagnosing endometriosis was 39.8 years. The risk of ovarian cancer was higher with early diagnosis and long-standing disease. However, women who had a hysterectomy before or by the time endometriosis was diagnosed did not have an increased risk of ovarian cancer [Melin et al, 2006]. Using the same register in 2004, Borgfeldt and Andolf quantified the risk of ovarian cancer in women with endometriosis. The odd ratio was 1.34 with a confidence interval of 1.03-1.75 which was a very modest increase in statistical terms. Many other similar reports have been published over the last decade including increased cancer risk not only in patients affected by endometriosis, but also in their close relatives. It is also interesting to note that endometriosis and cancer share few characteristics including cell invasion and uncontrolled growth, development of new blood vessels and decreased apoptosis [Varras et al, 2003]. A reassuring statement form Somigliana et al in 2006 in a critical review of all the available data, stated clearly that endometriosis should not be considered as a clinical condition associated with a clinically relevant risk of any cancer and the current management strategies should not be changed on the basis of these epidemiological reports. This statement has since been emphasised by new recommendations in the guidelines in ESHRE Information for Women (2014) which stated:

- There is no evidence that endometriosis causes cancer,

- There is no increase in overall incidence of cancer in women with endometriosis,

- Some cancers (ovarian cancer and non- Hodgkin’s lymphoma) are slightly more common in women with endometriosis (Good practice point).

The Guidelines Development Group recommended that clinicians explain the incidence of some cancers in women with endometriosis in absolute numbers (Good practice point).

The Guidelines Development Group also recommended no change in the current overall management of endometriosis in relation to malignancies, since there are no clinical data on how to lower the slightly increased risk of ovarian cancer or non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in women with endometriosis (Good practice point).

Bowel symptoms related to endometriosis

The bowel may be involved with endometriosis in up to 37% of cases with the rectosigmoid colon being the most commonly affected site. As well, it has been reported that in 30% of these patients another bowel site may be affected as well. The list includes the terminal ileum, caecum and appendix. Most bowel related symptoms seen in the chronic pelvic pain clinic are related to involvement of the rectosigmoid colon including:

- non cyclic pelvic pain

- painful defecation especially before and during menstruation

- constipation with premenstrual diarrhoea

- shooting pain up the rectum

- rectal pain during vaginal intercourse

- lower backache

- rarely rectal bleeding.

In many cases such bowel symptoms may be caused by prostaglandins or other inflammatory chemicals released by endometriotic deposits in other parts of the pelvis, without involvement of the bowel itself. Right iliac fossa pain may indicate involvement of the appendix, which should be inspected carefully during laparoscopy. Efforts should be made to do so, as it can be involved in adhesions or may be retro caecal in position. Gustofson et al (2006) reported 4.1% involvement of the appendix in cases with histologically proven endometriosis in other part of the pelvis, and in 3.7% of all women with right lower abdominal pain. The quoted figure for involvement of the appendix in the endometriosis group contradicts with the 20% figure quoted by Agrawal and Liu in 2003 for a corresponding group of patients. Once more, this may be due to differences in the diagnostic criteria used, or may even reflect a genuine difference related to the severity of the disease in the two populations. On the other hand, involvement of the caecum itself or terminal ileum is usually asymptomatic, but can cause vague lower abdominal symptoms and bloating sensation. Such symptoms may be cyclic, related to the time of menstruation

- The first laparoscopic image above shows a very early stage of rectovaginal endometriosis. There is a vertical ridge in the middle of the pouch of Douglas between the two uterosacral ligaments. This signifies the rectum being pulled up towards the upper part of the vagina and the back of the cervix. Note how the pelvis otherwise looks clean. Deep endometriosis is better felt than seen.

- The second image is a more advanced stage of rectal endometriosis than the first image. The rectal wall itself was invovled as shown with the dark deep area pulled up. A more proximal part shows superficial involvment of the rectal serosa with red endometrioisis. This patient had severe dyspareunia and dyskesia.

Urinay tract symptoms of endometriosis

The urinary tract was estimated to be involved with endometriosis in 20% of the cases with the bladder being the most affected site. This figure is equal to the risk of endometriomas yet it is not usually addressed by gynaecologists. It usually involves the peritoneal and subperitoneal tissues in the uterovesical pouch leading to bladder symptoms without any abnormal findings at cystoscopy. Accordingly, inspection of the uterovesical pouch during laparoscopy for that purpose is very important. It could show as actual endometriotic lesions or scarring of the peritoneal fold making it less stretchable when pulled up with a pair of grasping forceps. Symptoms related to bladder involvement include:

- Lower abdominal or suprapubic pain felt continuously or in relation to menstruation

- Increased frequency of micturition due to irritation of the bladder wall by endometriosis

- Abdominal pain when the bladder is full

- Lower abdominal pain during urination

- Suprapubic pain during intercourse due to mechanical irritation of the bladder bed

- Rarely haematuria would be a late sequel following deep invasion of the bladder wall.

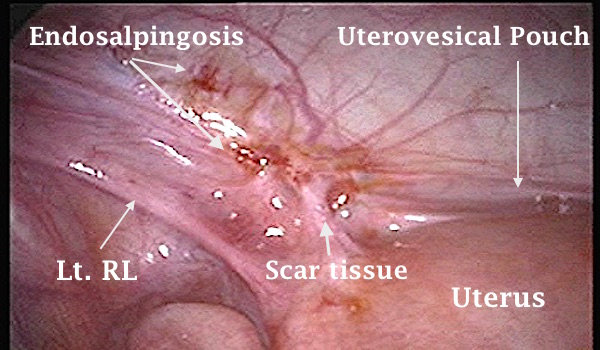

The first laparoscopic image shown below illustrates scarring of the uterovesical pouch with endometriosis before being excised, as shown in the second image. The diagnosis was confirmed histologically in this case. Sometimes only few red or black lesions can be seen on the surface. Pulling the uterovesical peritoneum with a grasper can reveal the extent of the subperitoneal lesions. This may cause difficulty during dissection of the involved area because of subperitoneal tissue scarring.

|  |

The ureter may be involved with endometriosis, but this is usually superficial on the overlying peritoneum or outer serosal layer. Deeper involvement can lead to stricture formation, following severe scarring of the neighbouring tissues. This can be released after excision of such tissues, without operating on the ureter itself. Furthermore, such scarring can put the ureters at risk of being damaged during gynaecological surgery. The lower part of the ureter is especially prone to be involved with endometriosis of the uterosacral ligaments. On the other hand, rectovaginal nodules larger than 3 cm in size are also prone to involve the ipsilateral ureter. Most of the blood supply feeding the ureters comes from small blood vessels on their lateral sides. Accordingly, dissection of the ureters may be vascularly safer, if done from their medial aspect.

The first two laparoscopic pictures above show involvement of the right and left ureters with endometriosis, respectively. Both ureters were seen only at their proximal parts, near the pelvic brim. The third image shows the left ureter after being cleared. It was a very difficult procedure. Diagnosis was confirmed histopathologically.

The above shown laparoscopic image depicts the right pelvic sidewall, with the right ureter kinked in its distal part, before being crossed by the right uterine artery. This patient had no related symptoms to this findings, but future complications leading to proximal hydro-ureter and right kidney problems were most likely, had the kink was not discovered and relieved.

As a general rule, ureterolysis should always be started at a healthy area, usually near the pelvic brim. Care should be taken not to devitalise the ureter during the procedure by over zealous pealing of the ureteric sheath, and hence its blood supply. Ureteric peristalsis is a reassuring sign of ureteric wall integrity following such surgery.

A special association between endometriosis and interstitial cystitis (IC) is becoming more evident over the last few years, without the bladder itself being involved with any endometriotic lesions. More information will be given about this subject later on during this website.

Other symptoms related endometriosis

It is not unusual for patients with endometriosis to present with other symptoms on top of their chronic pelvic pain and abnormal uterine bleeding. This could add to their sufferings and affect their quality of life. It could be useful to take note of the following symptoms and deal with them in a total illness management plan:

· A recent study showed women with endometriosis to be twice at risk to suffer from migraine headaches (38.3% vs. 15.1%) at a younger age of onset compared to a control group [Ferrero et al, 2004]. However, the severity and frequency of these attacks were not different between the 2 groups. A different study by Tietjen et al in 2007 looked at women with migraine headache as the study group and documented its correlation to endometriosis as well as other medical problems. They found higher prevalence of endometriosis in women with migraine than in non headache controls. Furthermore they found that women with migraine and endometriosis had more frequent and disabling headaches than women who had migraine but no endometriosis. Additionally, patients with migraine and endometriosis had more menorrhagia, dysmenorrhoea and infertility compared to other patients with migraine only and normal controls. The same was also valid for depression, anxiety, irritable bowel syndrome, interstitial cystitis and chronic fatigue syndrome.

· Other symptoms include bloating sensation, recurrent vaginal candida infections, allergies and food sensitivities and history of infectious mononucleosis. This is over and above an increased familial tendency to allergic manifestations [Lamb and Nichols, 1986]. This could qualify endometriosis as a pelvic disease with systemic manifestations. A review by Agic et al in 2006 revealed that patients with endometriosis had increased blood levels of C - reactive protein, TNF-alpha, IL-6, IL-8 as well as CD44+ and CD14+ monocytes with reduced levels of C3+ T lymphocytes and CD20+ B lymphocytes. This might explain some of the general manifestations frequently associated with endometriosis and the reason why it is considered a systemic inflammatory condition.

· Endometriosis may involve the upper abdominal cavity, and has been seen under the diaphragm. In such cases, it may cause pain in the affected area. Shoulder pain has also been reported due to irritation of the diaphragm with endometriosis. The liver itself may be affected with endometriosis. This is a rare complication reported by Nezhat et al, in 2005. Endometriomas in the ovary and liver have been described in the same patient before [Rovati et al, 1990]. Such lesions were reported in a woman, long time after she had hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy for pelvic endometriosis [Bohra and Diamond, 2001].

· Endometriosis can also involve the lungs, but this is not common. In such cases patients may present with chest pain, shortness of breath and haemoptysis, or pneumothorax during menstrual time. The right lung is usually more affected than the left one [Suginami H, 1991]. Catamenial pneumothorax was thought to be due to:

- Gaps in the diaphragm which allows air to pass into the lungs from the abdominal cavity during menstruation,

- Pleural lesions which have damaged the lung cortex leading to direct communication between the lung and the pleural space [Breton et al, 1990].

· Pancreatic involvement with endometriosis has also been reported after ultrasonic diagnosis of a cystic structure in the pancreas suspected to be a post inflammatory pseudocyst. Histological assessment revealed a diagnosis of endometrioma [Verbeke et al, 1996].

· Occasionally, the prolonged course of the disease and its disruptive effect on a patient's life might lead to depression, emotional problems and low self esteem.

The two laparoscopic images above show endometriotic lesions a little lower than the dome of the diaphragm, and at the dome itself respectively. Both patients had extensive pelvic endometriosis, but neither of them had related upper abdominal quadrant symptoms.

Diagnosis of endometriosis

As there are no reliable screening or conclusive diagnostic tests for endometriosis, a high level of clinical suspicion is necessary. This is especially so in women with adult onset pelvic pain, secondary dysmenorrhoea and deep dyspareunia especially if they had family history of endometriosis or other autoimmune problems. However, a recent report described some potential for serum antiendometrial antibodies as a screening test for endometriosis in patients with dysmenorrhoea, chronic pelvic pain and infertility. Randal et al (2007) reported a positive predictive value of 88%, negative predictive value of 86%, sensitivity of 87% and specificity of 87%. At the same time Florio et al (2007) used urocortin, which is a neuropeptide from the corticotrophin-releasing hormone group, to help with the diagnosis of endometriomas. Elevated plasma urocortin levels were detected in 88% of the cases with endometrioma with 90% specificity. The corresponding figures reported after using CA 125 in the same group of the patients were 65% and 90%.

As mentioned previously, a structured protocol should be used to help with the clinical diagnosis of endometriosis including:

- The pain questionnaire should address all systems reviews especially psychological issues and previous history of abuse. Other related concerns should be included as well. It is always useful for patients to fill the questionnaire at home without the intrusion of any other person. They should not exaggerate or belittle any of their symptoms or concerns. It is also important that they air their expectations and what level of pain they might be able to live with.

- A well-kept pain calendar is most valuable in revealing the timing, intensity and duration of pain. It can also reveal bowl, urinary or musculoskeletal symptoms and their relation to menstruation. This gives a clearer picture of all the systems involved and the level of disruption in the social or professional activities of the patient at different times of the month, especially in relation to menstruation. Describing such association from memory may not be very accurate.

- Pain mapping using pictures would show the site of maximum pain and tenderness and any referral pattern as well as extra pelvic sites.

These diagnostic aids do not cancel the need for a thorough clinical interview as mentioned before. This should be followed by pelvic examination during menstruation which is the best time to examine for nodularity and tenderness of the uterosacral ligaments or the rectovaginal septum. Both vaginal and rectal examinations would be necessary. Pelvic tenderness simulating the patient’s symptoms and pain during defecation or intercourse is a very helpful diagnostic finding and usually indicates local pelvic pathology. With a tender nodular pelvis and negative or positive chlamydia antibodies tests, endometriosis could be seen in 80% and 65% of the patients respectively. Furthermore, lateral axis deviation of the cervix with asymmetry in the size of the lateral fornices and narrowing of the posterior vaginal fornix are occasionally seen during speculum examination. This might follow unilateral scarring pulling the uterus to the same side or an adnexal mass pushing the uterus to the opposite side.

Transvaginal scan examination

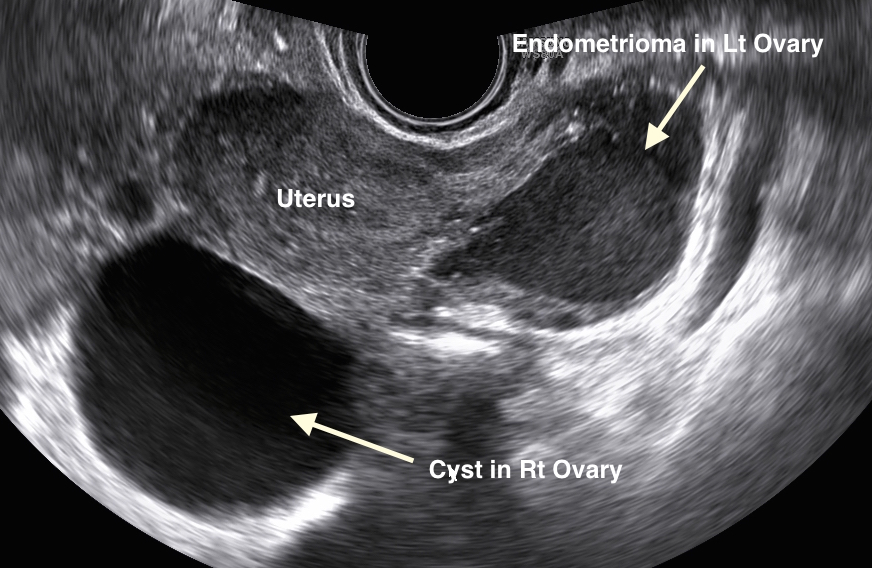

Transvaginal ultrasound scanning may reveal no pelvic abnormality but can show signs of pelvic adhesions in few cases. Furthermore, the probe can be used to elicit site-specific tenderness during examination conducted during menstruation. In 15-20% of the cases an endometrioma can be seen as a cystic mass with thick wall, homogeneous low-level internal echoes and occasional wall calcifications. This pattern is not specific and may be seen in other adnexal masses including dermoid and hemorrhagic cysts, tubo-ovarian abscess and ectopic pregnancies. Furthermore, anechoic cysts or cysts with some internal debris or septae and solid-looking appearances have been described in histologically proven cases of endometriosis. In this respect breakdown of the blood components within an endometriotic cyst may follow the same resolution pattern similar to any other haematoma. Accordingly, the final picture depends on the age of the patient and the endometrioma itself. The picture in postmenopausal women was described as one of heterogeneous internal echoes with central calcification [Asch and Levin, 2007]. Accordingly, there is no appearance exclusively specific to an endometrioma and the clinical picture should help in the final interpretation of the result. This confirms the importance of pelvic scanning being conducted by gynaecologists who can use the scan probe to extend their clinical judgement for the benefit of that particular case. It can also be used to elicit site-specific tenderness, and to test for pelvic adhesions. Once an endometrioma has been diagnosed ultrasonically, other parts of the pelvis are mostly affected by endometriosis in more than 90% of the cases. On the other hand, such a diagnosis can not be excluded if an endometrioma is not seen, as such ovarian cysts are usually seen only in 15-20% of patients with proven pelvic endometriosis.

- The first image below shows an endometrial cyst with low internal echogenicity and a small crescent like ovarian tissue extending between 6 and 10 o'clock. This is the more usual pattern seen with endometriomas, but by no means the only one.

- The second ultrasound image below shows an ovarian cyst with fluid level. This pattern is more common with dermoid cysts. In this case the cyst proved histologically to be endometriotic in nature.

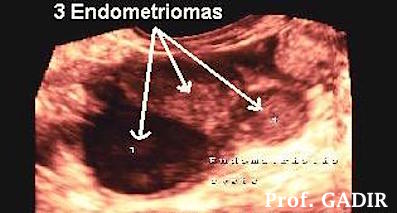

- The first image shows two cysts of different echogenicity. Initially the cyst on the left was described as endometriotic, while the one in the right ovary had all the characteristics of a simple cyst. The left side cyst was confirmed histologically to endometriotic. Interesting, the right side cyst was reported as a serous cystadenoma with superficial layer of endometriosis .

- The second colour image below shows three different histologically confirmed endometriomas in the same ovary. Note the difference between the dark looking one and the other two. Colour was used in this case to emphasise the different patterns of endometriomas even in the same ovary.

|  |

Other imaging modalities

Other imaging methods utilised for the diagnosis of endometriosis included CT scanning and MRI. However, CT scanning proved useless in this respect and is no longer a viable option. On the other hand MRI showed good potential in most but not all series. It was reported to be very sensitive and specific in showing endometriotic lesions as small as 3 mm in diameter by Arrive et al [1989] and Togashi et al [1991]. This allegedly made it very useful in exploring the extent of deep pelvic endometriosis, which is vital for planning surgical excision. However, this sensitivity was not confirmed universally. Another MRI study detected less endometriosis than laparoscopy and had 69% sensitivity and 75% specificity in detecting lesions confirmed histologically [Fielding, 2003]. This was not the experience of Marcelli et al [2006] who reported 100% sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing vesical endometriosis with 92% diagnostic accuracy for posterior nodules. Furthermore Onbas et al [2007] showed contrast enhanced dynamic MRI to be very sensitive to differentiate nodular endometriosis in the abdominal wall and pelvis from other pathological conditions. As for all other imaging facilities, technical factors, the experience of the radiologist involved and differences related to the location, size and texture of the endometriotic lesions may account for these different results. Despite all this controversy, MRI remains a very useful diagnostic modality especially in the diagnosis of deep endometriosis in the bladder bed and rectovaginal septum. This will help in the proper planning of surgery, bowel preparation, and the choice of the lead surgeon as well. On the other hand, MRI is expensive and can not be used as a routine first line investigation in all patients with pelvic pain. Proper patients’ selection can make it most cost effective and useful in the proper management of these patients.

Surgical diagnosis difficulty

It has often been stated that laparoscopy with tissue biopsy are the gold standards to diagnose endometriosis. However, certain criteria have to be adopted for patient’s selection to prevent misuse of this diagnostic procedure. Following a thorough clinical assessment, the following indications could be used:

- There is a strong clinical suspicion after using a structured protocol.

- When the symptoms affect the quality of life.

- Examination during menstruation elicited pelvic nodularity or site-specific tenderness similar to the patient's complaint.

- When ultrasound scan examinations revealed a pelvic abnormality.

- When an initial treatment with oral contraceptives and NSAID has failed.

- When new symptoms occur in a patient already diagnosed with endometriosis.

- Planned second look for completion of treatment.

- Infertility investigations especially in patients with chronic pelvic pain or those who had pelvic surgery in the past.

Pelvic endometriosis may show as atypical clear, white, vesicular, flame-like, yellow and red lesions. These patterns are usually seen in adolescents and in patients with recent onset of the disease and may spontaneously regress or grow according to the ovarian hormonal cycle [Evers, 1987]. Accordingly, extra care should be taken to avoid missing them. Occasionally, peritoneal defects are seen on the pelvic sidewall. These are known as Allen-Master windows and can be related to endometriosis. They were first described by Sampson in 1927 and since then they have been described by different authors. They were found in 7% of patient with chronic pelvic pain [Chatman, 1981]. Histological assessment of these pockets was done by Vilos and Vilos in 1995. Endometriosis was found in 39%, chronic inflammation in 20%, endosalpingosis in 12%, calcification in 4% and no abnormality in 25% of the cases. The typical black or brown lesions historically associated with endometriosis usually take many years to develop and are usually seen in adults many years later than the atypical ones. They represent haem degradation products as they undergo haemorrhage and fibrosis. On the other hand, dormant or healed lesions may look white or as calcified areas, made of remnants of glands embedded in fibrous tissue [Nisolle et al, 1995].

The three above shown laparoscopic images demonstrated different looks of Allen Master Windows. Nevertheless, the histology reports in all three cases showed endometriotic tissues with some chronic inflammatory cells. Some reports showed that similar lesions may show only scar tissues, probably due to burnt out endometriosis. Alternatively, the sampling might not have be deep enough to reach the deep lesions.

Historically, visual identification in 33% of all supposed endometriotic lesions did not satisfy strict histopathological diagnostic criteria [Fielding, 2003]. Accordingly, the advise was to excise, or at least biopsy all suspected lesions for histological confirmation of the disease before destructive surgery. This is especially so, as old suture material, carbon deposits following previous surgery, old blood and such conditions as endosalpingosis may all give the same visual appearance. This is especially so for endosalpingosis which is made of ciliated tubal tissue without any stroma. It was found in 7.9% and 7.3% of women with or without pelvic pain respectively [Hessling and De Wilde, 2000]. Accordingly, it is considered to have only a minor role in this respect. Over diagnosis of endometriosis is as bad as under diagnosing it, as patients will be liable to have unnecessary medical or surgical treatment in the future for the alleged disease. Furthermore, no more efforts will be made to find the real cause of the patient’s symptoms.

On the other hand, histological diagnosis of endometriosis may be fraught with many difficulties related to the presence or absence of the glandular component. This is demonstrated by ‘stromal or gland-poor’ endometriotic lesions. Furthermore, infiltration of the stroma by histiocytes and smooth muscles as well as peritoneal fibrosis, metaplasia and decidual changes may interfere with the histological picture as reported by Clement PB in 2007. The same author also reported some histological diagnostic difficulties when dealing with cervical, ovarian surface, tubal, intestinal and colonic endometriosis. This information can explain the negative histopathological reports occasionally received from the laboratory after examination of biopsies removed from areas with characteristic endometriotic appearances, and patient's who had favourable response to down regulation with GnRH-analogues. In recent years, both the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists and ESHRE recommended that diagnosis of endometriosis should rely on visual inspection by an experienced gynaecologist.

|  | Pelvic laparoscopic view of a patient with long history of pelvic pain and deep dyspareunia. The histology showed predominant chronic inflammatory cells with scanty endometriotic fossi. A diagnosis of gland poor endometriosis with endosalpingosis was suspected. The patient responded well after surgical excision of the affected area and downregulation with GnRH-analogue. |

| | |

|  | Laparoscopic view of a suspected endometriotic lesion in the left side of the uterovesical pouch medial to the left round ligament (Lt. RL). Histological assessment of the excised tissues showed endosalpingosis with no evidence of endometriosis. The patients presented with chronic pelvic pain. |

Anterior abdominal wall endometriomas

Occasionally patients may present with cyclical anterior abdominal wall pain during menstrual time. This is mostly felt along an abdominal scar following caesarean section or myomectomy. In such cases a tender mass will be felt and Carnett’s sign may be positive. High frequency ultrasound examination of the anterior abdominal wall may reveal a mass with different types of echoes. As with similar ovarian lesions, there is no specific characteristic picture for abdominal wall endometriomas. They may be echogenic, isoechoic or hypoechoic in comparison to the neighbouring tissues. However, the cyclical nature of the pain relative to menstruation with a previous history of pelvic surgery should raise the suspicion for making the diagnosis.

The differential diagnosis of such masses includes hernias, spontaneous haematomas, lipomas and desmoid tumours. However, the clinical history and ultrasound examination findings will be different for these pathologies. Anterior abdominal wall pain caused by nerve entrapment related to previous surgery will be discussed later on under the musculoskeletal causes of pelvic pain.

- The above first ultrasound image shows a circumscribed hypoechoic anterior abdominal wall mass, underneath a caesarean section scar, splitting the rectus sheath. It was immobile and very tender on palpation, especially during menstruation. The patient had 2 previous caesarean section operations, the second being 2 years previously. It proved to be an endometrioma on histological assessment. The uterus also showed an area of adenomyosis.

- The second ultrasound image above shows a well circumscribed solid mass in the rectus sheath. The patient also had 2 previous caesarean sections, the second one being 6 years previously. This mass also proved to be endometriotic in nature.

Note the difference between the echotecture of the two endometriotic masses. This may only be related to the differences in duration since the last caesarean section. Absorption of the the fluid over time, and deposition of fibrous tissue instead is the most likely explanation.

Perineal and vulvar endometriosis

Endometriosis could also be seen in episiotomy scars though this is not commonly reported. This possibility should be kept in mind especially in patients who complain repeatedly of a painful perineum after childbirth especially if an episiotomy had been performed. McCormick et al (2007) reported on 3 patients who presented with vague perineal pain adjacent to the episiotomy scars, 3-6 months after childbirth. Their symptoms got worse cyclically during menstruation and physical examination revealed vague fullness of the area. Endoanal ultrasound scan examination revealed a local mass with mixed echogenicity which proved endometriotic on histological assessment after excision. Though uncommon, they suggested that such a diagnosis should be kept in mind when dealing with patients who present with a painful perineum after childbirth. Similar case reports have been published of endometriosis involving a bartholin gland or the resulting scar following its excision by Matseoane et al in 1987; Goemen et al in 2004 and Buda et al in 2007.

Treatment of endometriosis

Endometriosis is an inflammatory progressive disease which can cause pain by different ways, depending on the stage and severity of the disease. Biochemically active lesions can produce prostaglandins, cytokines and substance P which can cause dysmenorrhoea and bowel symptoms. They may, as well, trigger afferent nerve pathways. Deep lesions can affect nerve endings directly causing more pain [Redwine and Sharp, 1971]. On the other hand, pelvic adhesions may affect tissues blood supply, and cause mechanical tension on small nerves [Olive et al, 1997]

The exact treatment of endometriosis depends on many variables including the patient’s age, her symptoms, fertility needs as well as the location and extent of the disease itself. Accordingly, the treatment plan should be tailored to suit the patient’s needs including:

- Pain relief,

- Restoration of normal or near normal anatomy,

- Maintenance or improving the fertility potential.

It is apparent that only surgical management may have a chance of fulfilling all these three requirements. But even so, this is not the case in many patients. On the other hand, medical treatment could be used to prevent further progress of the disease and to give pain relief in mild and moderate conditions. However, eventually surgery would be necessary to deal with such conditions as large endometriomas and deep endometriosis in the rectovaginal septum.

Medical treatment of endometriosis

Pain control is the cornerstone for the total management of patients with endometriosis. In most cases patients would have used over-the-counter medication for a long time before seeking medical advice. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) are usually prescribed first for that purpose in primary care clinics. They act by blocking the synthesis of prostaglandins which are important factors in causing pain. Different brands within this group are used including mefenamic acid, ibuprofen and naproxen. Some patients might respond or react differently to these drugs and a different one should be used in cases of side effects or ineffectiveness. They could be used to control dysmenorrhoea or in a time contingent plan for chronic non-cyclic pelvic pain. However, they might prove ineffective in many cases and more potent non-narcotic analgesia would be needed.

Hormonal treatment in the form of the oral contraceptive pill, progestogens including depo-provera, gonadotrophins releasing hormone analogues and danazol have all been used with good results but have different side effects which might not be acceptable to the patients. They are more effective when dealing with small endometriotic implants. They could reduce the size of the endometriotic lesion and the related inflammation as well as pelvic vascularity [Betts and Buttram Jr VC, 1980 and Cook AS and Rock JA, 1991]. They are all capable of reducing the actual or relative oestrogen supply to the endometriotic implants but each of them has a unique specific mode of action. Progestogens have the added effect of causing decidual exhaustion of the endometrial glands. On the other hand, danazol has a local androgenic effect on the lesions. The combined oral contraceptive pill is progestogen dominant and causes atrophy of the endometrium in the long term. This would reduce the monthly menstrual blood loss with less retrograde menstruation which could be useful after excisional surgery to remove endometriosis. They also block the enzymes cyclo-oxygenase type II (Cox-2) and aromatase which are necessary for the synthesis of prostaglandins and the conversion of androgens to oestrogen respectively [Maia and Casoy, 2007]. Accordingly, they could give symptomatic relief as well as reduce the progress rate of the disease. On the other hand, continuous use of a monophasic oral contraceptive pill proved to be safe and useful for patients who get pain with cyclic withdrawal bleeding. However, GnRH analogues are the ones mostly used now as they proved to be the most effective especially with dysmenorrhoea and dyspareunia [Vercellini et al, 1993]. They are given by monthly injections though certain ones could have an ultra long effect and could be given every 3 months. Nasal spray medication has been used in the past and is still available for those who prefer to avoid injections but are not practical alternatives, as two or more daily doses are usually needed. As well, efficacy could be affected by nasal congestion and catarrh. Furthermore, a patient might forget to use it or might not find the right circumstances in work or during travel to administer it unnoticed. They work by desensitising the pituitary gland reducing gonadotrophins secretion, mainly LH, leading to anovulation which would deprive endometriosis of its oestrogen supply. To prevent osteoporosis and severe vasomotor symptoms, patients should be offered an add-on medication to allow their prolonged use for 6 months or more. This is usually done in the form of low or high doses of progestogens, low dose oestrogen or combined oestrogen and progestogen medication. In essence these drugs are given as hormone replacement therapy to counteract the temporary and false menopausal state created by the GnRH analogues. Good pain control is usually possible during the GnRH-a medication period and could last for 6 months after cessation of the treatment but recurrence is almost certain thereafter. On the negative side, patients would not be able to conceive while using these drugs and hence they are not helpful in improving the fertility potential of the inflicted patient. Furthermore, as endometriotic lesions usually get smaller and change colour after such medication, they might be missed during laparoscopy compromising the chances of full excision. This is a drawback especially during second look laparoscopy to assess the effect of the first surgery and in patients with recurrent symptoms.

In recent years the levonorgestrel intrauterine contraceptive device mirena has been shown to reduce the symptoms and size of endometriotic lesions in the rectovaginal septum [Fedele et al 2001]. Furthermore, suggestions have been put forward to use it immediately after surgery to reduce the need for further operations in the future [Vercellini et al, 2003] as mentioned previously. Levonorgestrel has been found in the peritoneal fluid in significant amounts, approximately two-thirds of the serum level, in women who showed improvement in their symptoms after six month of using mirena [Lockhat et al, 2005]. Similarly, the level of the serum marker CA-125 showed equivalent decline after long term use of the device and GnRH-a for the treatment of endometriosis [de Sa Rosa e Silva et al, 2006]. All these effects were related to the high levels of peritoneal levonorgestrel causing atrophy of the ectopic endometrial glands, decidual transformation of the stroma as well as increased apoptotic activity. It has also been reported to have anti inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects [Vercellini et al, 2005]. Furthermore, levonorgestrel has been shown to decrease and then block DNA synthesis and mitotic activity by Bergeron C in 2000. The increased endometrial apoptotic activity related to levonorgestrel was found to be secondary to reduced expression of the Bcl-2 gene which has an anti apoptotic effect [Vereide et al, 2005]

Other new treatment modalities included aromatase inhibitors which have been used for the management of pelvic pain caused by endometriosis. Favourable response with reduction in pain intensity and size of the endometriotic lesions has been reported [Shippen and West, 2004]. Using an analogue pain scale, Amsterdam et al [2005] confirmed the same findings after using 1 mg anastrazole with an oral contraceptive pill daily for 6 months. In fact the mean pain scores started dropping after only one month of therapy. More important, they found no detrimental effect in the blood counts, liver and renal function tests, cholesterol level or bone density. Other experimental therapies used included selective oestrogen receptor modulators and anti progesterone medication RU 486 (mifepristone). However, they are all still tentative and more evidence is needed to support their wide scale use in such cases.

One could conclude this section by stating that the ideal medical treatment for endometriosis which could control the progress of the disease and give good symptomatic relief without affecting fertility in young women is not yet available. However, in an animal model the angiogenesis inhibitor TNP-470, endostatin, effectively interfered with the growth and maintenance of endometriosis [Nap et al, 2004]. One year later Becker et al (2005) showed 47% reduction in the growth of endometriotic lesions using the same drug, compared to a control group without affecting fertility. This was further confirmed by Jiang et al in 2007 who showed reduced expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in the ectopic endometrium. Such findings would hopefully pave the way for similar research in humans to limit the use of surgical interventions with their significant potential for adhesions formation.

Surgical treatment of endometriosis

Surgical management of endometriosis could be definitive by total excision of all the lesions or conservative by local destruction with laser or electrocautery. Some of the implants could extend 20 mm into the pelvic tissues especially in the rectovaginal septum and only total excision would allow effective removal of these deep lesions. Conservative surgery with preservation of the uterus, tubes and ovaries would be indicated for the younger age groups who still have fertility aspirations. This might entail incomplete excision and a higher risk of recurrence. Accordingly, patients should be counselled regarding the possibility of residual pain and the need for further surgery in the future. This would reassure them that treatment has not failed but was rather tailored to preserve or even improve their fertility potential.

During radical or definitive surgery all visible lesions and any suspicious peritoneal areas as well as the appendix should be removed. Such complete excision was found to give pain relief for up to 5 years but pain could recur earlier due to the formation of adhesions or any other cause without the recurrence of endometriosis. This was in fact shown by Abbott et al in 2003 as 36% of their patients needed further treatment but no further endometriosis was seen during second look surgery. Previously total abdominal hysterectomy and removing both ovaries was the standard method for treating severe endometriosis resistant to medical treatment and conservative surgery. This is no longer the case as removing the uterus does not remove the deep endometriosis implants in the pelvic sidewall, uterosacral ligaments or rectovaginal septum. This is expected, as endometriosis is an extrauterine disease in the first place. Nezhat et al [1994] reported that 34% of patients with chronic pelvic pain who had hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy in the past showed endometriosis during diagnostic laparoscopy. In the same year, Redwine DB [1994] came to the conclusion that endometriosis could remain symptomatic despite removing both ovaries, even without using any exogenous oestrogen, unless all deep endometriotic lesions were excised at the same time. He reported 33% intestinal involvement in such cases. In a more recent publication, Behera et al [2006] confirmed the persistence of endometriosis in many patients with chronic pelvic pain who had a hysterectomy and bilateral oophorectomy in the past. Other than the expected adhesions, endometriosis and ovarian remnants were the most common findings. It remains to be said that the uterus could be removed when the endometriosis is associated with severe adenomyosis or multiple symptomatic fibroids at the same time.

Management of ovarian endometriomas is a common dilemma especially in young patients. Emptying and flushing the cyst repeatedly and local destruction of the sac could be the preferred option in young women, as less ovarian tissue would be destroyed. This could be done with cysts 5 cm or less in diameter. However, with larger cysts the capsule should be removed if at all possible. This might be difficult at times as it might be stuck to the ovary by scar tissue. In such cases that part of the capsule should be excised with a sacrifice of some healthy tissue underneath. Alternatively, the cyst could be aspirated and flushed repeatedly during the initial laparoscopy and GnRH-a administered monthly for 3 months. Definitive surgery to remove the capsule could be arranged after that time when less tissue inflammation is expected and stripping the capsule might become easier. Before attempting any form of ovarian surgery the ovaries should be mobilised free of any adhesions to allow proper exposure of the pathology and to select the appropriate area to start the cystectomy.

As mentioned before, in the presence of ovarian endometriosis other parts of the pelvis may be involved in the majority of cases. In a large series of cases, only 1.06% of the patients who had ovarian endometriosis did not show any further lesions in other parts of the pelvis [Redwine DB, 1999]. The same author suggested that such lesions should be used as markers for extensive disease. Treating only the ovarian pathology would indicate underdiagnosis and undertreatment of the concerned patients.

The first image above shows enlargement of the right ovary with an endometrioma. The second picture shows the ovarian capsule being sliced to remove the cyst. Unfortunately it started leaking (figure 3), and its cotents needed to be sucked out, before the cyst capsule could be removed (Figures 4 and 5). The sides of the ovarian defect were not approximated (Figure 6), as ovaries usually heal best without adhesions, if not resutured [Brumsted et al, 1990; Wiskind et al, 1990 and Myer et al, 1991].

Deep endometriosis

This is a different entity of endometriosis and needs to be addressed separately. It is a term used to describe lesions infiltrating 5 mm or deeper under the peritoneum [Koninckx and Martin, 1994]. It is commonly seen in the uterosacral ligaments, the rectovaginal septum and beneath the bladder peritoneum. The pathology was described by Novak in 1974 as a combination of endometrial glands and stroma within a mass of fibromuscular tissue. However, Cullen described this concept of adenomyomas in 1927 to be followed by Sampson who suggested in 1928 that rectovaginal lesions were only secondary to infiltration of that part by endometriosis from neighbouring areas. Such lesions could involve the uterosacral ligaments first before spreading laterally or medially to engage the ipsilateral ureter or rectum respectively. As well they could begin in the pouch of Douglas itself before extending in different directions to involve all neighbouring tissues. The outer serosa and superficial longitudinal muscular layers are usually the most commonly affected parts of the rectal wall.

Deep endometriosis is more likely to cause chronic pelvic pain than endometriosis in other parts of the pelvis. Compression and infiltration of the nerves in the subperitoneal space by deep endometriotic lesions was suggested to be the direct cause [Fauconnier and Chapron, 2005]. Involvement of the rectum and bladder could cause symptoms related to these organs. Such location-indicating symptoms and site-specific tenderness could give good clues to the location and distribution of the endometriotic lesions. Furthermore, a positive correlation was found between the severity of dysmenorrhoea with the presence of deep endometriosis in the uterosacral ligaments and with the depth of their invasion [Leng et al, 2007]. Such lesions as well as nodules in the rectovaginal septum were also associated with dyschesia more than lesions in other parts of the pelvis.

The rectum might fuse with the posterior vaginal wall, the back of the cervix or even the uterus itself. Such lesions are also more likely to cause pelvic pain than endometriosis in other areas of the pelvis. This is especially so during intercourse and defecation with the pain mostly felt in the back. Shooting pain up the rectum is not uncommon. Sometimes pain is felt only before or during menstruation. Rectal bleeding is a very unusual presentation of deep endometriosis. It is best diagnosed by combined vaginal and rectal examinations to feel for any indurations in the rectovaginal septum, the pouch of Douglas or uterosacral ligaments. Slight upward pushing of the cervix with the finger in the vagina would stretch the uterosacral ligaments and make them easier to feel with the finger in the rectum. It is more useful to conduct this examination during menstruation otherwise there is 50% risk of getting false negative results. The importance of such timing has been stressed by Koninckx et al in 1996.

Unfortunately transvaginal scan examination and barium enema might give false negative results depending on the site and extent of the disease. The role of MRI has already been discussed before. In comparison to rectal scanning it proved to be more accurate for the diagnosis of uterosacral and vaginal endometriosis where as both were equally accurate for the diagnosis of colorectal endometriosis [Bazot et al, 2007]. However, neither MRI nor rectal scanning had absolute diagnostic accuracy, but they are still very useful adjuncts to vaginal and rectal examinations. As well, there is no biochemical test which is specific or sensitive enough to help with the diagnosis of deep endometriosis; hence a high degree of clinical suspicion is needed. Occasionally, a nodule could be felt on one side or the other while the patient is under general anaesthesia before starting laparoscopy. This might not be possible in the clinic because of the immense pelvic tenderness. However, nodules in the upper part of the uterosacral ligaments and rectal wall might not be felt during vaginal or rectal examinations [Chapron et al, 2002]. As the lesion is retroperitoneal, its true extent might not be possible to assess laparoscopically and complete excision should be ascertained by vaginal and rectal examinations during the procedure.

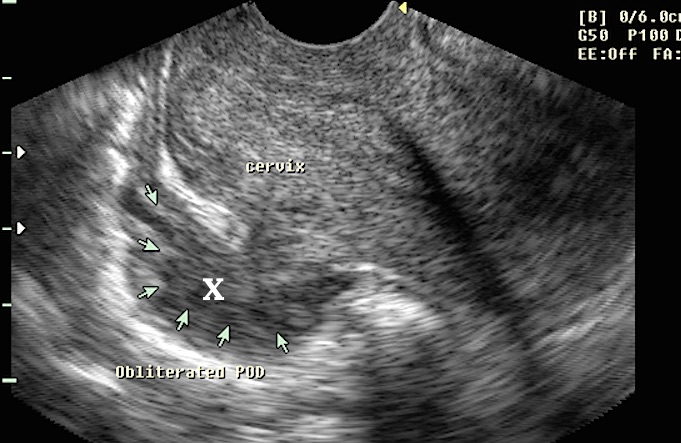

- The first ultrasound image shown below demonstrates extensive rectovaginal endometriosis as seen during transvaginal ultrasound examination, marked as X.

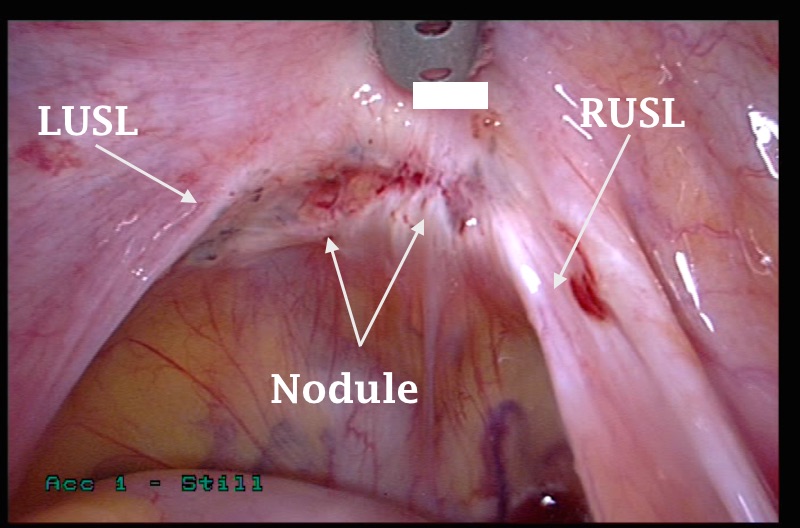

- The second image shows an endometriotic nodule medial to the right uterosacral ligament (RUSL). The bulk of the nodule was felt vaginally. To deal with such a lesion, the technique should isolate the uterosacral ligament from both the ipsilateral ureter and the rectum, before it can be excised. The advice 'Do not attack the pathology' is most important in such cases, as both the ureter and rectum may be damaged.

|

|

A normal pouch of Douglas usually extends down behind the upper one third of the vagina. Accordingly, a good part of the posterior vaginal wall would be seen between the rectum, the back of the cervix and the two uterosacral ligaments. For that reason, a swab on a stick pushed up the posterior fornix would show how much of the vagina is visible laparoscopically. This part of the vagina is also covered by an upward extension of the rectovaginal septal fascia which goes on to form part of the posterior pericervical ring and extends laterally to fuse with the uterosacral and cardinal ligaments [Richardson et al, 1993]. Rectal adhesions to the posterior vaginal wall or the cervix would cause partial or complete obliteration of the vaginal wall respectively. With partial obliteration part of the vaginal wall would be seen where as with complete obliteration the outline of the sponge on the stick in the posterior vaginal fornix would not be seen laparoscopically. This test is more accurate than simple visual assessment of the pelvis in verifying the extent of obliteration of the pouch of Douglas. Furthermore, using a probe into the rectum could help to identify the extent of rectal wall involvement. The outer serosa would move freely on top of the probe in cases with no or only superficial involvement. Alternatively, with deeper lesions involving the inner muscular layer and mucosa itself, the serosa would not move as freely on top of the probe.

Deep rectovaginal endometriosis is usually divided into 4 stages with no distortion or obliteration of the pouch of Douglas in the first two stages. However, a correct diagnosis and staging may become possible only during the microdissection of the nodule during surgery. The 4 stage are:

- Stage 1 with no vaginal involvement.

- Stage 2 involves the vagina.

- Stage 3 involves the vagina and rectum with cul-de-sac distortion.

- Stage 4 as for stage 3 plus cul-de-sac obliteration.

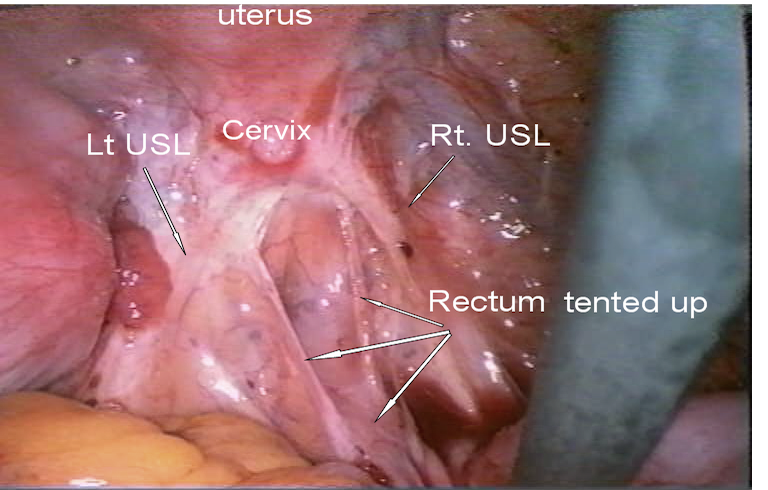

Early stage of rectovaginal endometriosis with the rectum shown tented up. Still most of the upper part of the vagina could be seen underneath the posterior part of the cervix between the two uterosacral ligaments |  |

|

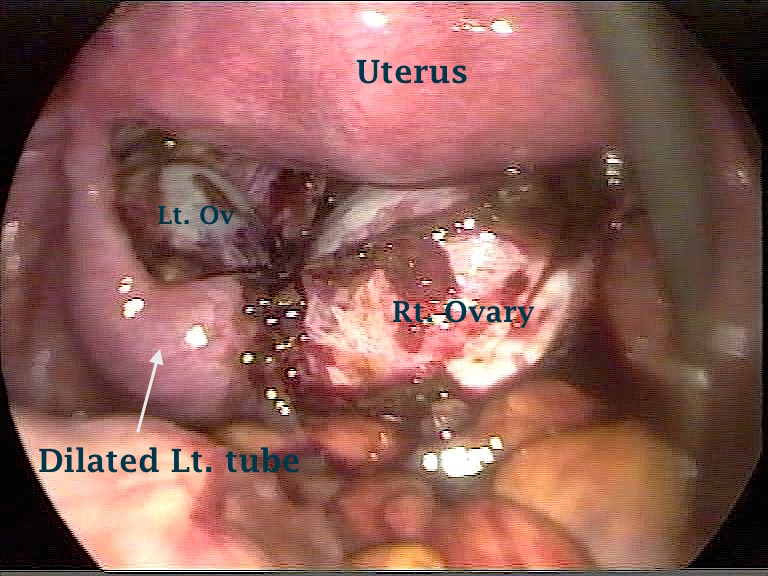

Severe pelvic adhesions do not necessarily indicate involvement of the rectum or vaginal wall with deep endometriosis. Accordingly, total reliance on visual assessment may give a wrong diagnosis in many cases. The neighbouring laparoscopic picture is a good example of such a case, with no rectovaginal involvement at all. This patient attended for infertility reasons, rather than pelvic pain. It was reported by Redwine and Wright in 2001 that 27% of their patients who had complete obliteration of the pelvis with endometriosis did not have rectal involvement.

|  |

|

For comparison purposes with the picture above, the neighbouring image shows the rectum pulled up and attached to the posterior vaginal wall and posterior aspect of the cervix. A nodule was felt high up in the posterior fornix behind the cervix by vaginal examination. Despite infliction with deep endometriosis the pelvis looked almost normal. Furthermore, this patient had intense deep dyspareunia and dyskesia. |  | |

Treatment of deep endometriosis

Treatment of deep endometriosis could be difficult and entails thorough planning in advance. It is important to remember that deep endometriosis does not mean involvement of the rectovaginal septum in all cases. In fact such involvement occurs in only a small percentage of all deep endometriotic lesions [Chapron et al, 2001]. The majority of lesions would be in the uterosacral ligaments. Accordingly over zealous attempts to reach that area would be unnecessary in most cases.